Chad (not his real name) and I dated in high school. Now we’re friends on Facebook. We do the normal Facebook things, like sending happy birthday wishes, sharing and commenting on cute old photos, and retelling funny stories from the carefree days of youth. Everything was going fine, until… Election 2016. In the last year, our communication has gotten tense. Chad is one of those people…on the wrong side of the issues; you know… a real “nut job.” I know when I post some political article or call to action, Chad will protest angrily in the comment section, frequently in all CAPS! It’s frustrating. He just won’t listen to reason. Funny thing is, he says the same about me. He recently wrote that he feels like if he tries to debate with liberals, “I will be labeled a racist and woman hater! There is no room for dialogue…the left is totally intolerant, to the point of writing off lifelong friends!” He said he gets worked up because he is not anti-woman but he’ll be accused of that and worse if he mentions “anything opposing the left!” So, my question: does he have a point?

Chad (not his real name) and I dated in high school. Now we’re friends on Facebook. We do the normal Facebook things, like sending happy birthday wishes, sharing and commenting on cute old photos, and retelling funny stories from the carefree days of youth. Everything was going fine, until… Election 2016. In the last year, our communication has gotten tense. Chad is one of those people…on the wrong side of the issues; you know… a real “nut job.” I know when I post some political article or call to action, Chad will protest angrily in the comment section, frequently in all CAPS! It’s frustrating. He just won’t listen to reason. Funny thing is, he says the same about me. He recently wrote that he feels like if he tries to debate with liberals, “I will be labeled a racist and woman hater! There is no room for dialogue…the left is totally intolerant, to the point of writing off lifelong friends!” He said he gets worked up because he is not anti-woman but he’ll be accused of that and worse if he mentions “anything opposing the left!” So, my question: does he have a point?

I have to admit, when Chad posts an article or video and asks me to read or watch it, I don’t. I assume it’s probably about some crazy conspiracy theory. I usually just move on to the next person in my feed that is speaking my language. It just feels so good to be understood, doesn’t it? In 2017, it is easy to find news and information that we agree with. Any hour of the day or night, we can read articles, listen to podcasts, soak up social media or watch news and talk shows that reinforce our feelings. It wasn’t always like this. There was a time when most Americans were consuming the same news shows, and those news shows were legally required to be balanced. Did you know that we used to have a thing called the “Fairness Doctrine” in the United States? This article explains how the FCC set up the Fairness Doctrine in 1927 to make sure that any party with access to the airwaves presented both sides of a controversy. It also insured that if an individual were being attacked personally in a broadcast, they would have the chance to defend themselves on the same program (Matthews, 2011). As the Fairness Doctrine was weakened in the 1980s, conservative talk radio was born, and biased broadcasting of every kind followed. Now there are media soapboxes of every ilk, and we find ourselves in a country with competing realities. We used to disagree about issues; now we are literally arguing over what is fact and what is fiction.

Setting aside the current administration, politicians, those who perpetrate oppression and discrimination, sinister operatives, shady cover-ups, and other past and present offenses that we feel outraged about, let’s talk about the rest of us – most of us – we the people. Wherever we reside on the political spectrum, we the people have urgent concerns about our children’s futures, our country, and our safety. In the current highly charged atmosphere, we may find ourselves seeking out the opinions we want to hear and shutting out all the others. I certainly do! Unfortunately, if we opt for this kind of voluntary brainwashing, we help to propagate the demonization of those with opposing views. This is the worst thing that can happen between us. The divide is growing; it’s a frightening problem, which isn’t getting better on its own. How can we alter our course?

Give it up; People don’t care about “reason”

Once in a while, I spend some time in an effort to reach ‘across the aisle’ to Chad. I craft words to explain as thoughtfully and gracefully as I can what I think are very reasonable ideas for him to consider. As I write, I strain to filter out any antagonistic language. I figure if I can just be diplomatic enough, he’ll acknowledge that I have a point. My neck and shoulders are tense by the time I put the finishing touches on my little missive of logic. I post it. You know what I get back from Chad after all that work? A bunch of gibberish in ALL CAPS! It’s not really gibberish, but it may as well be. I don’t understand it, and I don’t want to understand it. I see that my efforts are fruitless, I feel drained, and I wonder, “Why do I even bother?”

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt says we can’t convince other people to “listen to reason,” because people are not motivated by reason. In his book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, Haidt (pronounced like “height”) lays out the case that people don’t use reason as a guide but as a way to explain what they’ve already decided based on their moral intuition (Haidt, 2012). Other research supports Haidt’s finding that our political views are not fueled by rationality. A USC study examined participants’ brain activity as their political beliefs were challenged. The scientists found a link between heightened activity in the amygdala, an area of the brain “especially involved in perceiving threat and anxiety” and resistance to changing beliefs. The participants were more open to changing their beliefs about the world in general than they were about their political views. Researchers noted that, like religious beliefs, political views are part of personal identity. They concluded that “emotion plays a role in cognition and in how we decide what is true and what is not true” (University of Southern California, 2016). So this would seem to indicate that we seek out the facts (or even the non-facts) that support our emotional position about politics. But if we’re not motivated by reason, what drives us to see things the way we do? Haidt believes that all of us – liberals, conservatives and people in between – are motivated by morality. We simply focus on different aspects of morality.

The “Moral Matrix”

I don’t like labels, and certainly not everyone falls into these categories of “liberal” and “conservative,” but I’d like to use them here, in order to delve a little more deeply into Haidt’s ideas. In a 2008 TED TALK, “The Moral Roots of Liberals and Conservatives,” Haidt describes his work with fellow researcher, Craig Joseph, studying morality across disciplines, cultures and even species. They developed what they describe as the “five foundations of morality” (Haidt & Joseph, 2008). Haidt believes these five systems, intuitions, are present in the “first draft” of our minds; in other words, we are born with them. Cultural experience shapes how we express them (TED, 2008). As Americans, some of us may not immediately recognize all of these ideas as essential to our lives, but Haidt argues that they are “common in history and across the globe” because they reflect human nature (Saletan, 2012). The longer I look at them, the more I see them expressed in various aspects of my behavior. They are Harm/care: Being neurologically and hormonally designed to care for others (especially the vulnerable), we all “have strong feelings about those who cause harm.” Fairness/reciprocity: Human beings from religions around the world know some version of the golden rule. In-group loyalty: As a remnant of our tribal heritage, we come together and cooperate in groups (to fight other groups). Sports provide a way to exercise this tribal instinct. Authority/respect: This includes relationships where one party (a student, for example) is voluntarily deferent to another (a teacher). Purity/Sanctity: This one includes any ideology that promotes “attaining virtue by controlling what you do with your body.” Haidt says social conservatives may moralize about sex, but they do not corner the market on purity/sanctity. Many on the political left have utilized this principle to moralize food choices, aiming for the purity of organics, raw foods, etc. (TED, 2008).

Haidt and colleagues, Nicholas Winter and Ravi Iyer, have collected survey data from tens of thousands of people around the world, and they find that people who identify as liberal score very high on the first two moral foundations: harm/care and fairness/reciprocity. In fact, liberals are often willing to forfeit in-group loyalty, authority/respect and purity/sanctity (which they tend to distrust and interpret as xenophobia, authoritarianism, and puritanism) in order to pursue care and fairness. They champion the weak and oppressed, and their focus is global. Conservatives score higher on in-group loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity than liberals. They feel compelled to protect institutions and traditions that maintain order, safety, and stability, and their focus is local, parochial. Even though conservatives have the same instinct for caring and fairness that all humans do, they score lower than liberals on harm/care and fairness/reciprocity, because they are trying harder to balance all five of the moral foundations (TED, 2008). Said another way, “when it comes to morality, conservatives are more broad-minded than liberals” (Saletan, 2012). This is not a perfect study. The large number of respondents makes it substantial, but the fact that it is taken by self-selection indicates that it may include “little representation of the poor, working class, or lower-middle class” (Edsall, 2012). In spite of that particular weakness, Haidt’s ongoing research is compelling. There can be no doubt that Americans are divided, and he believes that both viewpoints (liberal and conservative) are crucial to our society. “Each side is right about certain things but then it goes blind to other things” (TED, 2016). Bottom line: we need each other to make our country work well.

So, perhaps Chad has been pointing to something valid in his frustrated ALL CAPs rants. Haidt’s research does indicate that the liberal focus on morality is narrow. He cautions those on the left, “If you think that half of America votes republican because they are blinded in this way (by religion or stupidity), then my message to you is that you’re trapped in a moral matrix” (TED, 2008). A moral matrix, says Haidt, is a “consensual hallucination” we get stuck inside when we only associate with people who think like us. Conservatives have moral matrices too. From inside a moral matrix, we agree on the wrongness (read: racism, dishonesty, corruption, ignorance, etc.) of those who disagree with us, and we look for facts that back up our strong feelings. Our moral matrix might be blue or it might be red; either way it keeps us stuck in righteousness and makes us more likely to demonize others. Chad and I are still “friends” on Facebook, but it seems like we are living inside different moral bubbles. When he comments on one of my posts with a rant that lumps me into a category with all “liberals,” it hurts. It’s clear that he also feels stung by the labels being assigned to him.

Disagreement to Disgust; a Dangerous Devolution

There have been times when we all got along better. The Americans who grew up during World War II, written about by Tom Brokaw in The Greatest Generation, experienced the losses and hardships of war, but also a shared survivorship, a sense of all being in it together, on the same team. Those folks went on to be the business leaders of the mid-20th Century, and the bipartisan climate of the country back then reflected their willingness to cooperate with each other (TED, 2016). A confluence of several factors has driven us to the deeply divisive place we find ourselves in now. Haidt cites the retirement of the WWII generation, purification of the two parties, and social media as some of the causes. Research shows that people are moving to live closer to others who think like them, which exacerbates the problem. Whatever the causes of this growing chasm, blaming each other is not helping.

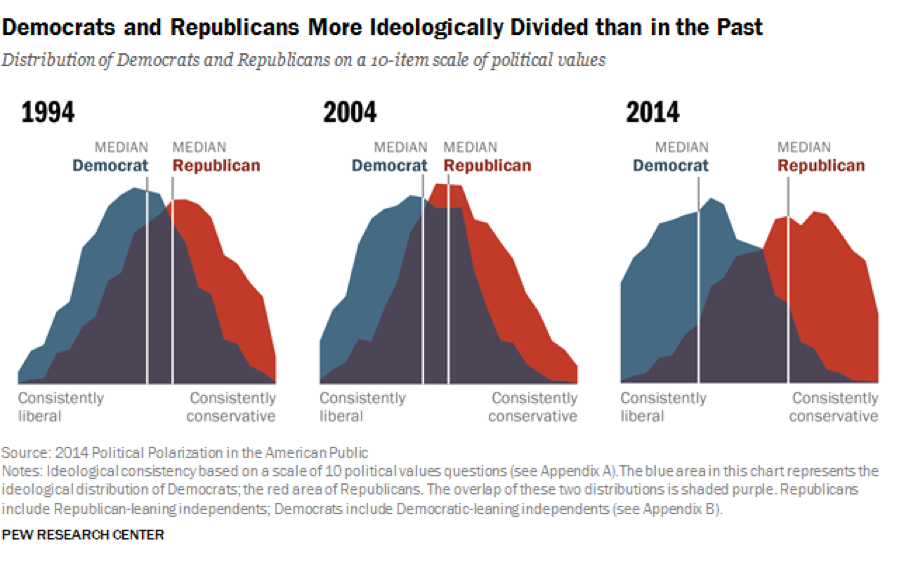

Many people agree that political divisiveness has never been worse in our country. We’ve moved beyond disagreement into something more dangerous: disgust. Pew research illustrates that ideological overlap between the two parties has decreased in the past 20 years, as partisan animosity has grown. More people on both sides have a highly negative view of the other party, to the point of agreeing that they are “so misguided that they threaten the nation’s well-being.” This is happening on both sides. In a 2016 TED TALK, “Can a Divided America Heal?” Haidt discusses the danger of this trend toward dualistic, us vs. them thinking, “Disgust reduces the other to sub-human.” The notion that our political differences constitute a fight between good and evil “makes us more likely not to just say ‘they’re wrong,’ but we say ‘they’re evil. They’re satanic. They’re disgusting. They’re revolting.’ And then we want nothing to do with them” (2016). We need to pivot. We are demonizing whole groups. The key to bridging the chasm is to get to know individual people.

There is Hope (and it involves fun)

One day, after a fruitless exchange with Chad, I had an idea. What if we deliberately had fun with people with opposite political views? I envisioned small groups of 8 to 10 people, all over the country, made up of half liberals and half conservatives. They get together to have fun. They go bowling, do karaoke, or share cookouts. Perhaps they choose a charity project to do together, practice mindfulness exercises together, or help each other with home improvements. Most importantly, they do not talk about politics, at least not for a long time, until they consider themselves good friends. And then, once they’re friends, they are less inclined to judge all “liberals” or all “conservatives, and they’re more willing to give each other the benefit of the doubt.

We have serious challenges, and we can’t address them effectively when we hate each other. Jonathan Haidt believes that this divisive hatred is our most urgent social problem right now. He says love is the opposite of disgust, and that our hope lies in making the effort to drop our fear and reframe the way we see others. He recommends reading How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie and then reaching out to just one person on the other side of the aisle at a time (your uncle, your sister, a friend) and connecting with them through gracious communication. He says, “Read Jesus, Buddha, Marcus Aurelius,” anything that helps you learn how to empathize. Empathy is easy when it’s aimed at your preferred class of victims, he says, but it really counts when you generate it for your “enemies” (TED, 2016). He also advocates a return to the old practice when members of congress lived in and brought their families to Washington. Why does he recommend that? So those congress members and their families can socialize with other members’ families and establish a friendly, cooperative baseline for working together (Saletan, 2012). Haidt has created the website, www.civilpolitics.org, as a resource of ideas and actions anyone can take.

When I was hunting for pictures to use in this article, I searched the term “image of smug liberal woman,” and what I found, shocked me. Each time I found a fitting picture, it was associated with an article depicting liberal women as the scum of the earth. Living in my moral bubble as I have been, I was shocked to see the intensity of the vitriol. My research into Jonathan Haidt’s theories helped me to adjust my reaction from knee jerk to big picture. I didn’t spend much time counter-judging. And I remembered a comforting tidbit: When people feel safe, they get more progressive (TED, 2008). So I simply turned my focus back to my new idea. I love my idea, with its national scale, and in my mind, I can see it catching fire and changing everything for all of us right now. In reality, I don’t have the time or resources to make my grand idea happen right now, and solving this problem of division and hatred will be a slow process. But I bet I can create one bipartisan group in my town and start having fun with them. I can invite Chad and some of his friends. Perhaps, you can form a group in your town, too. Or maybe you can simply reach out to one person that you have been judging and offer your hand in friendship. I know it takes energy and trust and generosity to venture out of our bubbles. But we the people are worth it. People are good. That’s what we “narrow-minded” liberals believe.

References

Edsall, T. B. (2012, February 6). Retrieved March 1, 2017, from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/02/studies-conservatives-are-from-mars-liberals-are-from-venus/252416/

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York: Pantheon Books.

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2008). The moral mind. In The Innate Mind, Volume 3 (pp. 367–392). Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/95e4/74f37b362b6c4d53984d19bc147f7d256f13.pdf

Matthews, D. (2011, August 23). Everything you need to know about the fairness doctrine in one post. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-fairness-doctrine-in-one-post/2011/08/23/gIQAN8CXZJ_blog.html?utm_term=.90043a6f6975

Political polarization and personal life. (2014, June 12). Retrieved March 2, 2017, from http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/section-3-political-polarization-and-personal-life/

Political polarization in the American public. (2014, June 12). Retrieved March 1, 2017, from http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/

Saletan, W. (2012, March 23). “The righteous mind,” by Jonathan Haidt. Sunday Book Review. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/25/books/review/the-righteous-mind-by-jonathan-haidt.html

TED (2008, September 18). Jonathan Haidt: The moral roots of liberals and conservatives Retrieved from https://youtu.be/vs41JrnGaxc

TED (2016, November 8). Can a divided America heal? | Jonathan Haidt Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-_Az5nZBBM&t=30s

The Righteous Mind (2011). How you can help. Retrieved February 26, 2017, from http://righteousmind.com/applying-moral-psych/how-you-can-help/

The greatest generation. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/b/brokaw-generation.html

University of Southern California. (2016, December 23). Hard-wired: The brain’s circuitry for political belief. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 8, 2017 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/12/161223115757.htm